Why You’re Not Actually Doing Two Things at Once (And What You’re Really Doing Instead)

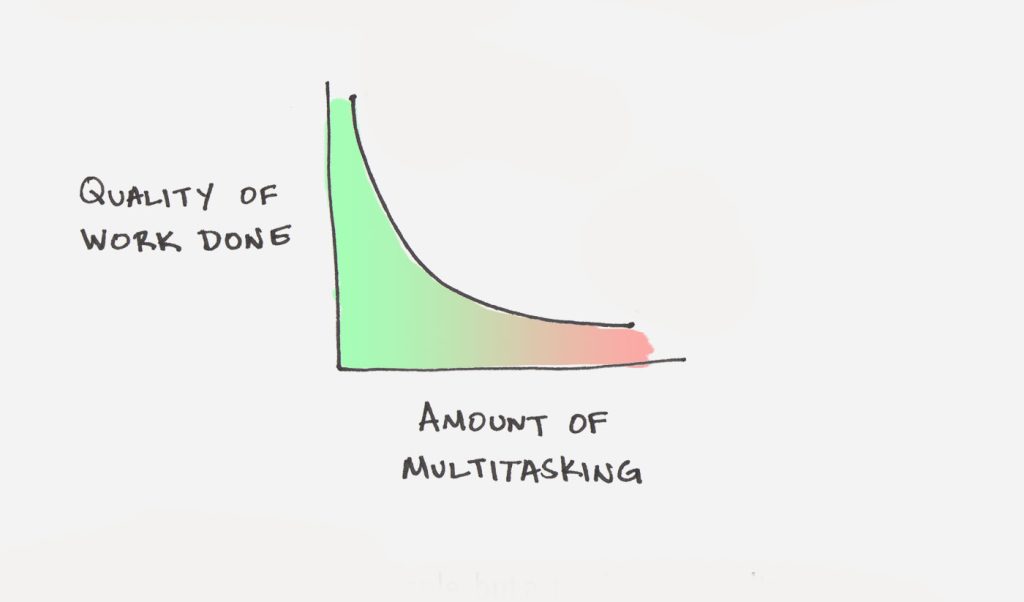

It’s a modern badge of honor: “I’m great at multitasking.” We scroll through social media while watching TV. We answer emails during Zoom meetings. We listen to podcasts while cooking dinner. I used to proudly include “excellent multitasker” in my own self-description—until cognitive science gently but firmly informed me I was lying to myself.

The truth is, what we call “multitasking” is a cognitive illusion. And understanding this isn’t just academic—it reshapes how we work, learn, and live.

What We Think We’re Doing vs. What’s Actually Happening

The story we tell ourselves: “I’m efficiently handling multiple tasks simultaneously.”

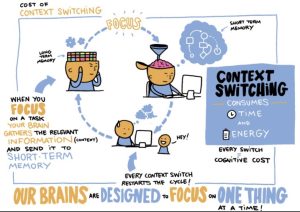

What cognitive science says: You’re task-switching—rapidly shifting attention between tasks, with a cognitive cost each time.

Think of your attention not as a wide beam floodlight, but as a laser pointer. You can point it at one thing, then quickly swing it to another, but you can’t point it at two things at once without the beam splitting and dimming.

The Cognitive Cost: Why “Multitasking” Makes You Slower

Researchers at Stanford University found something startling: people who regularly “multitask” are actually worse at it. In psychology, multitasking is considered as a myth. They’re more distractible, less able to filter irrelevant information, and slower at switching between tasks than people who multitask less frequently.

Why? Because every switch has a price—what psychologists call “switching costs.”

What happens during a task switch:

-

Goal shifting: “I’m going to do this instead.”

-

Rule activation: “Now I need the rules for this new task.”

-

Attention reorientation: Physically and mentally redirecting focus.

This takes time—anywhere from a few tenths of a second to several seconds per switch. Multiply that by dozens or hundreds of switches daily, and you’ve lost significant cognitive capacity.

Try This Simple Experiment (Right Now)

Let’s experience switching costs firsthand:

Part 1: Time yourself writing: “Cognitive science is fascinating” 10 times.

Part 2: Now time yourself alternating between letters and numbers: Write “C” then “1,” “o” then “2,” “g” then “3,” and so on through “Cognitive science is fascinating.”

What you’ll likely find: Part 2 took significantly longer, even though you wrote the same number of characters. That extra time? That’s your switching cost.

The Three Types of “Multitasking” (And Why Two Are Still Myths)

-

Parallel Processing: Doing two automatic tasks simultaneously (walking and talking)

Reality: Only possible when one task is automatic (doesn’t require conscious attention) -

Serial Task-Switching: Alternating between tasks requiring attention (email then report then email)

Reality: This is what we usually call multitasking—and it’s inefficient -

Background Tasking: Doing a primary task with background stimulation (music while studying)

Reality: Can help or hinder depending on the tasks and the person

The Hidden Impact on Memory and Learning

Here’s what really convinced me to change my habits:

When we try to learn while multitasking, information often goes to the wrong part of the brain.

Without distraction: Information → hippocampus (where memories are processed and stored)

With distraction: Information → striatum (where habits and procedures are stored)

This means you might recognize information later (“I’ve seen this before”) but not truly understand or recall it meaningfully. As a learning enthusiast, this was my wake-up call: my “multitasking” study sessions were creating the illusion of learning without the substance.

The Multitasking Brain: A Quick Neuroscience Tour

Functional MRI studies show what’s actually happening:

-

Prefrontal cortex: The “conductor” of attention—it can only conduct one “piece” at a time

-

Anterior cingulate cortex: Helps monitor conflicts—works overtime during task-switching

-

Basal ganglia: Involved in habit formation—gets confused with rapid switching

When we force our brains to “multitask,” we’re essentially creating neural traffic jams.

Gender and Multitasking: Debunking Another Myth

“Women are better multitaskers”—you’ve heard this. The research consensus? There’s no significant difference in multitasking ability between genders. Any differences observed in daily life likely stem from social expectations and practice, not cognitive architecture.

Practical Implications: What This Means for Your Daily Life

For Work:

-

That “quick” email check during deep work can cost 15+ minutes of refocus time

-

Try instead: Designated email blocks (e.g., 10 AM, 2 PM, 4 PM)

For Study (From One Learner to Another):

-

The “I study with TV on” method creates fragile learning

-

Try instead: 25-minute focused sessions with 5-minute breaks (Pomodoro Technique)

For Relationships:

-

Phones during conversations reduce connection and memory of the interaction

-

Try instead: Phone-free meals and dedicated conversation time

For Driving:

-

Hands-free doesn’t mean risk-free—conversation itself is the distraction

-

Try instead: Silence or passive listening during challenging driving conditions

The Exception: When “Multitasking” Actually Works

There’s one scenario where combining tasks can be beneficial: pairing an automatic physical task with a cognitive task.

Examples that work:

-

Walking while brainstorming

-

Knitting while listening to an audiobook

-

Simple cleaning while on a hands-free call

Key factor: The physical task must be truly automatic (doesn’t require decision-making or attention).

My Personal Multitasking Detox (And What Changed)

For two weeks, I conducted an experiment:

-

Week 1: Tracked all my multitasking attempts

-

Week 2: Eliminated intentional task-switching

What I noticed:

-

Tasks took less total time (even though they felt longer while doing them)

-

I made fewer errors (no more sending emails to the wrong person!)

-

I remembered more of what I read and heard

-

I felt less mentally fatigued at day’s end

The biggest surprise? I didn’t accomplish less—I accomplished more with less stress.

Your First Step Toward Better Focus

You don’t need to eliminate all multitasking overnight. Start here:

The Single-Tasking Hour: Choose one hour today. During that hour:

-

Silence notifications

-

Work on one primary task

-

When your mind wanders (it will), gently return to the task

-

Notice how you feel afterward

The Deeper Psychological Truth

Multitasking is largely considered as a myth, as a human brain is generally unable to focus on two demanding task simultaneously, leading to rapid task-switching that reduces efficiency and increases errors. Our addiction to multitasking isn’t just about efficiency—it’s often about avoidance. Switching tasks provides dopamine hits, relieves boredom, and helps us avoid difficult or emotionally challenging work.

Ask yourself: When I reach for my phone while working, am I seeking information or escape? Am I genuinely being productive or just avoiding something harder?

A More Honest Narrative

Instead of “I’m great at multitasking,” perhaps we could say:

-

“I’m learning to focus deeply”

-

“I respect my cognitive limits”

-

“I give important tasks my full attention”

This isn’t about perfection. It’s about awareness. Some days I still catch myself scrolling while on a call. The difference now is I notice it, name it (“Ah, task-switching”), and gently return my attention.

Your Challenge: Notice the Switch

For the next 24 hours, simply notice each time you switch tasks. Don’t judge it. Don’t necessarily change it. Just observe:

-

What triggered the switch? (Boredom? Difficulty? Notification?)

-

How did it feel to switch?

-

How long did it take to re-engage with the original task?

Share your observations in the comments if you’d like. Did anything surprise you?

In a world designed to fragment our attention, choosing focus isn’t just a productivity hack—it’s an act of cognitive rebellion. And it starts with recognizing that our brilliant brains, for all their wonders, truly can only do one conscious thing at a time.